Because we're big....the size delusion

- Nick Keppel-Palmer

- Feb 28, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 21, 2021

Get married for love

For much of my working life I've wrestled with the problems of partnership - or rather the wrong partners in business. I think collaboration is one of the most powerful forces in business but all too often I see businesses make terrible choices in which partners they collaborate with.

One of my favourite brands was a little Norwegian electric car maker called Think who made ahead-of-their-time electric city cars.

The Norwegians loved it - but as in many aspects of life they were a long way ahead of anyone else. So Think struggled commercially, got sold and resold a couple of times, and ended up with a bunch of owners who wanted them to "get much bigger".

So they cast about for a distribution partner who could help accelerate their entry into other markets and - inexplicably - settled on a tie-up with a kind of cash'n'carry warehouse store brand called Migros.

(Photo by Eduardo Soares on Unsplash)

On paper maybe there was some logic to it - we need sales, you've got shops; you need a bit of eco-cool, we've got that - but it's still very hard to see how this marriage came to be regarded by anyone as a good idea. Needless to say it did not work - and Think is no more.

I was always taken aback by how much care a business would put into choosing its CEO or key staff - checking for alignment and shared values - compared to how very little of that soft stuff they would think about when it came to key partnerships in critical areas like 'selling our precious product'.

If businesses chose partners based on a common way of thinking, shared interests, and not on a knuckle headed "you're big" they'd all be a lot better off.

Distribution partners - repent at leisure

Who sells your product can make a massive difference to your whole business - and not in a good way. And all too often it's super hard to spot.

As we have been developing the Good Growth Company we have been looking with a critical eye at every aspect of business chains. The conclusion we come to is that partners really, really matter. So much so that I'd say with confidence that the critical factor in building any good growth business is finding and choosing and engaging the right partner at every point in the chain. One wrong partner in a critical link and the whole system gets screwed up.

This can mean:

investors - so many good businesses have been and continue to be ruined by taking money from the wrong folks and being forced to dance to a different tune

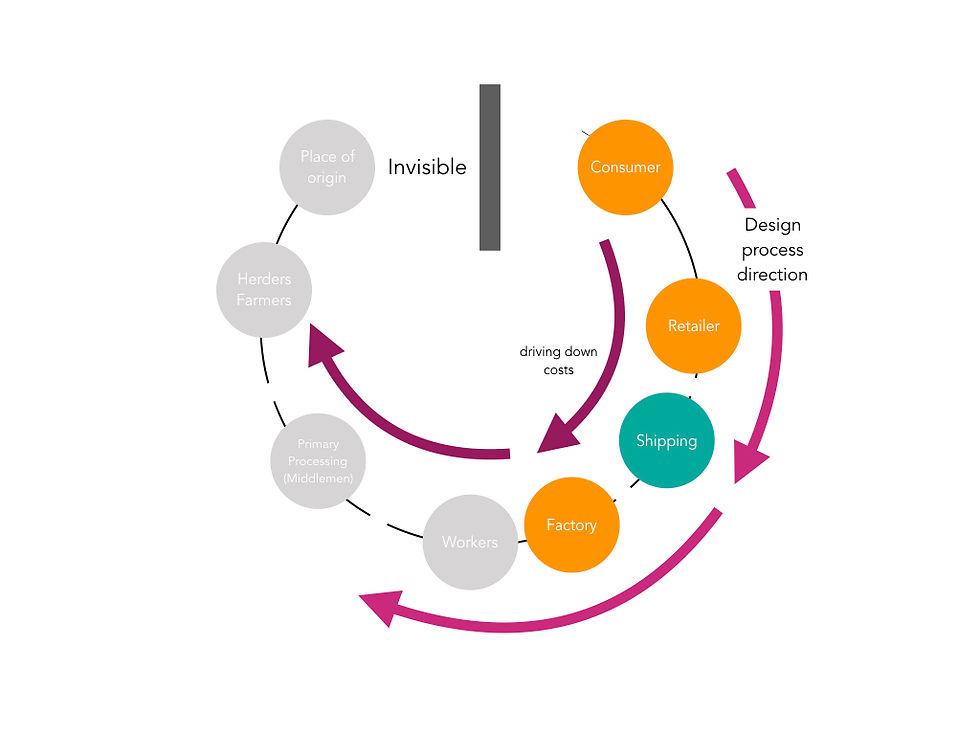

supply chain - the wrong processor can wreak havoc on small producers in pursuit of economies of scale. Primary processing becomes a transaction based on scale rather than a value add step in the chain. (For example the gigantic washing machines used to wash wool - these become mini-monopolies in the chain and act as such)

distribution - especially for products that derive a lot of their value from story of origin. If you end up with a distribution channel that does not support that story not only does the value you create get lost, but worse the distributor starts to influence how you make the product. I think distribution exerts a malign influence on brands that many are unaware of

A lot of our effort is going in to trying to align and 'unfragment' these chains to get everyone pointed in the same direction - it's surprisingly hard.

(there's a lot more about this stuff here)

"But we're really big"

I've been having a lot of fun working with the wonderful folk who make wine in Georgia. Wine is category where producers make a fabulous product, and should be able to exert significant influence over how that product gets sold, but all too often do not.

One of the striking oddities in wine is how much influence (good and bad) the distribution partners can exert over the product and the strategy. From China to Russia to Japan to Germany to the UK the in country distributors wield massive influence over where and how the product gets sold.

In the US especially there are a plethora of wineries and in relative terms not many distributors. The maths means that each distributor is being courted by many wineries. The rules - a hangover (sorry) from Al Capone's time - are rigid and insist on strict controls in each state. Meaning that for wine producers looking to import into the US middle men are baked into the equation - each wanting a healthy margin. So the commercial equation is especially tough.

The local producers (of whom there are many, and who themselves struggle with overcapacity and a younger population more interested in cannabis than the grape) can avoid many of these margin takers by selling a healthy proportion direct. A decent Napa winery will sell 65-70% of their product direct to people visiting or who have joined their club.

Not so for importers. 100% of what they sell goes through the importer-distributor-retailer system, and in a different way in each of the 50 states. They have to find distribution partners who can work in the right channels and present their brand to the right kind of customer with the right story. But this is cripplingly hard:

In wine there is a high volume price driven channel which sells off the shelf, and a hand sell channel through independent retailers which allows for stories to be told. They are very different channels catering to very different segments.

Wines from unfamiliar places with unfamiliar grapes don't do well in supermarkets.

Yet too many distributors try to push them through that channel - at tiny or negative margins - and with monstrous marketing costs.

It's a killing zone for brands

When asked why any producer would want to do this - sacrifice any hope of making any margin, send additional funds to the sellers for shelf promotions, be told to make the wine cheaper to be able to duke it out in the ferocious price war - the answer is:

"because this is a really big market"

Which is nuts

Size really does not matter - what counts is shared interest

At the same time as I was first wrestling with the weird asymmetrical influence that distributors exert over producers in wine (asymmetry of margin vs risk especially) this refrain of "because we're really big" was getting a regular outing in the Brexit and free trade agreement discussions.

One of the oft repeated assertions in the UK was that the EU, specifically the Germans, would want to treat the Brits kindly "because we buy a lot of cars". Another - fascinatingly repudiated on the BBC World Service - was that Commonwealth countries would want to switch trade to the UK post Brexit "because we're a really big market".

"Why would we want to do that?"

.....came the retort from a group of economists and trading folk from various places in Asia and Asia Pacific that had had some kind of colonial connection with the Brits a long time ago, but who had been busy over the past 40 years or so forging strong partnerships with their geographic neighbours.....

"we want to trade with people who share the same values as us, who care about the same things"

Don't we all?

Comments